This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

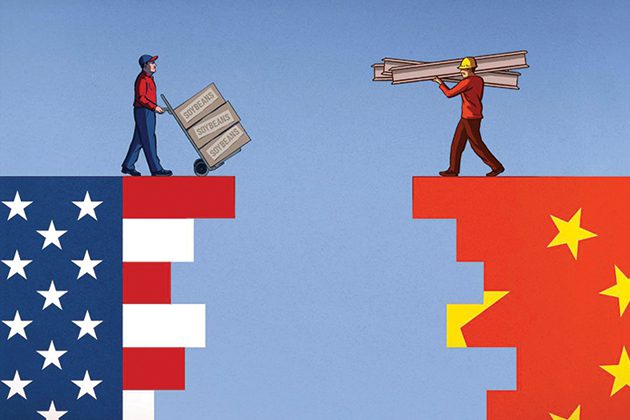

In March, the Trump administration sparked an outcry by announcing that it would impose import tariffs of 10% on aluminum and 25% on steel, following earlier tariffs on solar panels and washing machines. Representatives from the retail, automobile, manufacturing, construction and information technology industries, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and various trade groups all expressed concerns about the potentially detrimental effects of the tariffs.

Although the stated intent of the tariffs was to protect American workers and the U.S. economy, not everyone was convinced. Financial markets plummeted after President Trump tweeted on March 2 that “trade wars are good, and easy to win,” and other governments, including key allies, spoke out against the move. In a complaint filed with the World Trade Organization, South Korean officials labeled the steel tariffs as “unjust” and “inconsistent with the United States’ obligations.” The Chinese Commerce Ministry declared the tariffs “a serious attack on normal international trade order” and immediately slapped tariffs on 128 U.S. products in retaliation. Subsequent and sometimes contradictory comments from the Trump administration about whether the tariffs will actually be imposed, and against what nations, exacerbated market volatility and overall uncertainty.

The fallout could have a significant impact on U.S. companies. For example, analysts at Goldman Sachs reported that Ford and General Motors alone could see a combined $1 billion hit attributed to increased steel prices, which could ultimately have an effect on auto sales and industry jobs, while the American beer industry, which packs more than half of its products in aluminum cans and bottles, estimated that the tariffs would cost brewers nearly $348 million a year.

Widespread Impact

Of course, tariffs do have their supporters, with many believing levies on imported goods—particularly from China—are long overdue. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) reported 34,143 import seizures for intellectual property rights violations in 2017, an 8% increase over the previous year. Based on the manufacturer’s suggested retail price, this amounted to a total financial impact of $1.3 trillion, or $3.8 million worth of intellectual property rights violations per day.

These make up the majority of all import seizures and, according to DHS data, China is the top country of origin (although it is important to note that country of origin is not necessarily the same as where the seized goods were produced). “When you look at that, something has to change,” said Jennifer Diaz, international trade attorney and founder of Diaz Trade Law. “China on the whole needs to understand how important intellectual property compliance is, and they need to respect it more.”

Others believe, however, that the problems tariffs can create outweigh the benefits. According to Dr. Emily Blanchard, associate professor of business administration at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, the risks of U.S.-borne tariffs are significant and the effects can be more widespread than they initially appear. “Often, the conversation focuses on just those firms that are making the goods facing the tariffs in question,” she said. “The simplistic view is that, when we import less from overseas, that is good for local business. Of course, that has never been true for the whole economy—while a few import competing firms will gain from facing weaker competition, the aggregate cost of tariffs outweigh the benefits to those few. Domestic exporters, for one, stand to lose.”

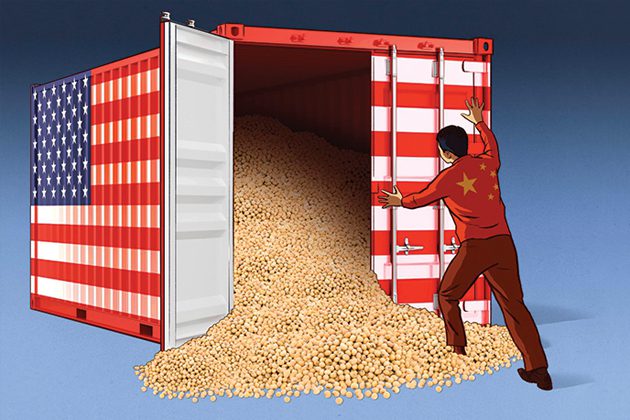

In the case of this latest round of tariffs, an unlikely assortment of U.S. businesses could be impacted. For example, after China proposed a 25% tariff on U.S. soybeans, crop futures fell amid worries about declining demand since China is the leading importer of U.S. soybeans. Last year, China bought about one-third of American soybeans, to the tune of $14 billion. Soybean prices dropped 4.5% after the tariffs were announced.

In the case of this latest round of tariffs, an unlikely assortment of U.S. businesses could be impacted. For example, after China proposed a 25% tariff on U.S. soybeans, crop futures fell amid worries about declining demand since China is the leading importer of U.S. soybeans. Last year, China bought about one-third of American soybeans, to the tune of $14 billion. Soybean prices dropped 4.5% after the tariffs were announced.

U.S. vintners are also concerned about losing access to the lucrative Chinese market, where a rising middle class has been developing a taste for American wines. “Vintners of the world are busy building brand equity in China,” Blanchard said. “Losing market share today may last.”

Then there are pig farmers. Blanchard believes the pork market will be one of the hardest hit. “This is relatively small in dollar terms, but hogs are really important because China buys a lot of stuff from pigs that nobody else buys,” she said. The market can be particularly volatile for American hog farmers and prices will react quickly to loss of demand from China. The market for offal, for example is reliant on Chinese consumers, which is reflected in current prices. But should farmers lose access to Chinese consumers, it is not clear who else would be willing to purchase offal and at what price.

Unfortunately, even if the U.S. government does scale back on its tariff threats, the damage may have already been done. “The moment you start talking about increasing tariffs for U.S. businesses, the risk is already there,” Diaz said. “U.S. companies that import are impacted, period.”

Supply Chain Concerns

The impact of tariffs is much broader because companies have increasingly complex international supply chains to consider. “Most companies don’t necessarily source 100% of what they make in the same country that they make it,” Diaz said. “It’s physically impossible in the global world we’re in today. Typically, everybody imports something that goes into the final product.”

Tariffs can disrupt these supply networks and create additional costs. “Tariffs are especially risky with very complex and deeply intertwined global value chains,” Blanchard said. “When policy changes disrupt an industry’s ability to import vital inputs, they can jeopardize the whole value proposition for local businesses. It’s really hard to predict these effects in advance, which makes it an especially risky game to slap tariffs on parts and other intermediate inputs.”

Even companies that believe they source domestically could be in for a rude awakening, said Gabrielle Griffith, director at global trade consulting and compliance firm BPE Global. Many U.S. manufacturers have discovered that, while they may be buying from a domestic source, the actual materials in question are being imported.

Such value chains carry risk in both directions. For example, when the United States increases its tariff on solar panels from China, some of the costs of that tariff may ultimately be borne by American resource suppliers that sell the necessary parts and components to Chinese solar panel assembly factories. “Pick a company, any company: Virtually any multinational you can imagine is making products that incorporate value added from around the world—very much including the United States—regardless of where final assembly takes place,” Blanchard said.

Such value chains carry risk in both directions. For example, when the United States increases its tariff on solar panels from China, some of the costs of that tariff may ultimately be borne by American resource suppliers that sell the necessary parts and components to Chinese solar panel assembly factories. “Pick a company, any company: Virtually any multinational you can imagine is making products that incorporate value added from around the world—very much including the United States—regardless of where final assembly takes place,” Blanchard said.

And for those companies that both import and export, the pain will clearly be felt on both sides of the equation. “There is a domino effect to consider, and it applies to everyone, domestic or international,” Griffith said.

Individual companies can expect to feel some pain in their supply chains. For those that rely on relationships with partners in China, South Korea or another country not exempted from the tariffs, sourcing and procurement practices must be assessed from the ground up and may have to be completely revamped. This could affect everything from finance and tax strategies to operational issues around establishing new warehouses and shipping/receiving operations in other locations. Every factor must be reviewed and measured against the potential risks.

With every product, how much a tariff affects U.S. consumers or firms depends on the elasticity—or potential substitutability—of both demand and supply. “How much would Chinese consumers suffer, for example, if it’s harder to get soy from the West? It depends on whether there are other countries that can step in to sell the same volume and quality at the same price,” Blanchard said. “Likewise, if a U.S. farmer can’t sell soy as easily to China, where is the next potential buyer? If there are other buyers waiting in the wings, no problem. If not, then U.S. farmers may have to accept substantially lower prices.”

Small but important industries could be crippled by tariffs and trade wars. “Once we dig in to see how much this would hurt American businesses, we can see lots of potential vulnerabilities,” she said. “Sometimes it’s just a question of volume. China is a huge buyer for a major U.S. product like soy. Sometimes there are critical global value-chain links, like the fact that there are no other markets for that product. In the longer run, we might worry that highly differentiated U.S. firms could lose their brand equity with Chinese consumers.”

Risk Management Considerations

No matter the size of their business, risk managers should be looking closely at their supply chain. “Know your manufacturing, know if you are global, know what you’re importing, know where you’re importing from, and now layer in the risks and the hazards,” Griffith said. “That’s going to drive supply chain decisions.”

Diaz added that compliance within the supply chain is critical and suggested that risk managers conduct a supply chain audit. Importers should understand the customs valuation and classification of the goods being imported and/or exported, what is being reported to customs, and the liability they are taking on. Companies should also look for ways to redesign products or find other sources for key goods so as not to fall victim to newly imposed tariffs. “Think about who you’re buying from and whether you have alternatives,” she said. “Think about who you’re selling to and whether you really need to enter the U.S. market, or if you can take advantage of foreign trade zones or bonded warehouses. Get creative with your supply chain. Everyone is going to have to be more nimble and flexible as they try to figure out what truly impacts them and how to get around it.” One way to get creative, she said is to understand if your company is importing to consume or importing to export elsewhere, such as importing to Miami to export to South America. These arrangements could be altered or streamlined to avoid increasing costs.

Another thing risk management can do, Blanchard said, is wait. Policies can change just as quickly as they are enacted. “Wait on the investment, on new hiring, on undertaking any kind of fixed cost, to the extent that is feasible,” she said. “It may not be ideal for the overall economy or employment, but sometimes it’s the smart play for the businesses in question.”

Blanchard also suggested diversifying risks by minimizing exposure to the United States as much as possible. “If you’re a multinational corporation and you have affiliates in China that are sources, that means you may not want to source inputs just from the United States for fear that China may apply retaliatory tariffs,” she said. “If you are a multinational firm with foreign affiliates in China and you’re selling to the United States, you should probably look around for your plan B market, to see if there is another place to sell.”

Companies should also examine their growth initiatives with a top-down review by risk management. “You have to know your business inside and out in terms of what you’re paying and where it came from,” Griffith said. “From there, you can make the best strategic decisions.”

[…] The Business Impact of Trump Tariffs “Biden new tariffs on China. President Biden […]