This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

Of all the dangers that consume risk managers’ thoughts, cybersecurity is arguably the most intangible. It is difficult to truly “see” the many factors that can cause breaches or attacks, which often leaves cyberrisk confined to the realm of hypothetical and worst-case scenarios. However, we continue to hear about successful attacks that penetrate enterprise security layers and put corporations’ fortunes, futures and reputations at stake.

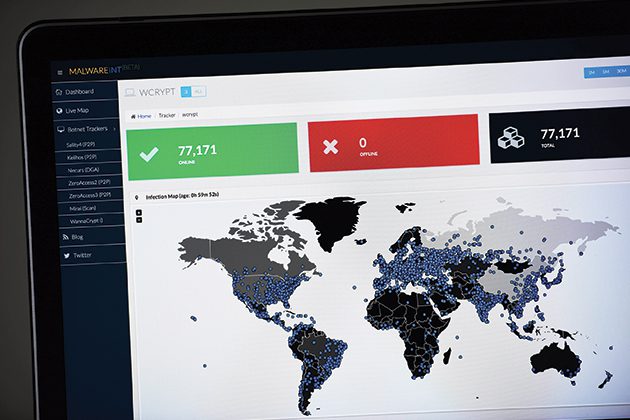

Recently, for example, when hundreds of thousands of computers around the globe were infected in the WannaCry ransomware attacks, businesses learned a painful lesson regarding the vulnerability of their IT assets and business-critical systems.

When these cyber crises strike, affected risk managers typically respond by connecting with technology, legal, C-suite and other stakeholders in their organizations. Sometimes an incident is so severe that it puts an entire industry on notice and prompts response drills among peer companies. Yet, once the firestorm subsides and the drills end, recognition of the need to better manage cyberrisk tends to fade into the background—until the next attack.

While it is impossible to completely eliminate risk, many business executives, chief information security officers (CISOs), attorneys, board members and risk advisors are working diligently to get a more strategic handle on forecasting the worst cybersecurity dangers and demonstrating their preparedness to management. Four principles in particular are emerging as critical for successfully managing cyberrisks:

1. Anticipate business leaders’ three most urgent questions.

The moment a CEO learns of a cybersecurity issue, the first three questions are going to be “What happened?” “Did we fix it?” and “What is the exposure?” Anyone versed in IT security, auditing, compliance and other risk disciplines can easily read between the lines here.

The first question is really asking “What is the most severe threat?” It could be a high-profile strain of ransomware, for example, or it could be evidence that files containing valuable intellectual property were inappropriately accessed and copied. The question is crucial for the wider risk management dialogue because it determines what the follow-up steps will be. For example, restoring infected devices that are disrupting customer orders requires a very different response than working with law enforcement after a break-in that spared operations but stole trade secrets.

“Did we fix it?” means “Can we stop the threat with our current controls?” Whether we are talking about finance, law or cybersecurity, the strength and adaptive nature of internal controls is paramount. When things go awry, you have to be able to determine whether existing controls were lacking, if the threat was somehow able to bypass prescribed controls, and whether adjusting the current controls can conclusively remediate the problem.

Risk managers know this from the physical world. If companies suspect an employee is committing fraud, investigators check to see if accounting, human resources or other policies were violated, or may have helped to curtail attempted embezzlement or kickbacks. This often requires quick collaboration with the heads of many office departments. Similarly, in the wake of a network intrusion, a security team must quickly gather data about where a suspicious file or user traveled on the network—and what happened at each stop—to eradicate any lingering malicious programs and verify that the situation is back in hand.

The “exposure” question is about damage control. Does a company have more of a nuisance situation, such as using data back-ups to bypass ransomware, or is this a breach with harsh legal, regulatory or trust implications? This all depends on the business, but the more closely security experts and risk managers work together, the more quickly they can move forward.

2. Unite views of the business.

Risk managers and security teams should meet regularly with leaders from across the company to discuss new technology initiatives and potential exposures. Cyberrisk is the greatest example of the need for cross-functional teams to tackle issues such as risk management and crisis response across the organization. Risk managers in any large company know that it is already challenging to keep the C-suite, general counsel, corporate communications and facility managers on the same page. It gets even more complicated when you add the internet of things as this expands the cybersecurity purview of the CISO to include “smart” connected buildings, production machinery and vehicles. And all of this could be linked to business operations, supply chains and other areas, accessing data and creating exposures companies may not recognize.

3. Use risk management context to throttle IT complexity.

Risk executives and cybersecurity professionals often focus on “context” and “complexity”—and in that order. When you are a risk manager, any number of issues could require an urgent phone call. The trick is to use context to determine which issue is most critical and to quickly take that to the right leaders for their guidance.

Likewise, cybersecurity leaders look for danger in a sea of complexity. Picture a tangle of computers, apps, mobile devices, cloud computing—with everyone requiring shared access. This is the inevitable result of business transformation. But make no mistake, complexity is the enemy of security. The deluge of traffic, the din of alerts and the sheer scale of IT assets make it hard to keep a close eye on everything. With many IT decisions and change factors being driven by different corporate sponsors, technology is always reaching past the security perimeter.

This has created an opportunity for risk managers to join forces with cybersecurity teams and use the deeper risk context to serve as a check and balance on complexity. Without this teamwork, corporate technology tends to sprawl, and risks that should have prompted harder questions are only apparent after the fact.

Consider the WannaCry attacks, which highlighted that vulnerable devices running old, unsupported software were still deployed across industries. How many organizations knew the true size of the target this outdated software placed on their backs? And, if they knew the size of the bull’s-eye before WannaCry hit, how many of them would have updated or replaced some of those devices had they realized?

But those who criticize any use of older, more vulnerable software miss the point. Sometimes, older versions of applications have to be used. For example, if they are baked into devices such as ATMs, x-ray equipment or industrial control systems, then they cannot be easily upgraded or abandoned. Here, security and risk experts can advise business leaders that necessity might outweigh the danger. Conversely, if you apply the same context to applications found running retail payment systems, for example, CISOs and risk advisors can make the case that tolerating the complexity of old code is a gamble not worth taking.

4. It takes a village to address the spectrum of cyberrisks.

Executives and network defenders point to a spectrum of cyberrisk flashpoints. At one end of the scale are risks introduced by technical factors, such as the discovery of a severe vulnerability in a core business application, or employees using personal devices that lack appropriate security controls. By themselves, these gaps seem slight, but they can lead to problems. At the other end of the spectrum are risks triggered by business operations. Business leaders must make decisions every day to retool supply chains, encourage telecommuting or open overseas offices. These seemingly straightforward business decisions can upend cybersecurity policies and postures that were adequate just a few months earlier.

Technical and business leaders who handle cyberrisks are starting to recognize that stakeholders need to work together. It is simply too difficult to measure—let alone manage—cyberrisk if we rely on old assumptions that buying more security products will improve safety or that a business unit can figure out the risks of a project on its own.

Whether conducting a post-mortem on WannaCry and bracing for its sequel, or answering tough boardroom questions on how secure the company is after years of data breach headlines, it is clear that cybersecurity leaders and risk managers have their work cut out for them. Fortunately, they also have an opportunity to help each other by coming together and applying their unique perspectives and expertise to the challenges at hand. This is the philosophy the risk management community needs if we are to manage the risks of doing business in a world of digital ransoms, robbers and hard realities.