This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) went into effect on May 25, 2018, and despite the publicity and prognoses of doom, it did not have any immediate earth-shattering effects. At most, you may have noticed a flood of requests to re-subscribe to websites or to review a company’s updated privacy policy. In fact, many non-EU-based businesses may not even notice that the GDPR is now effective because they have been dismissing it as a regulation that “does not apply to us.” This is a serious misperception—a significant number of businesses in non-EU countries, including the United States, are subject to the regulation and its potentially massive fines. There is an expectation that European data regulators will look very closely for violations and may not be shy about imposing significant fines on companies that fail to comply.

The GDPR is in many aspects quite similar to the data breach notification laws in the United States, although in some aspects, the regulation is considerably broader. As cyber insurance has developed to respond to expenses and liabilities related to data breaches in the United States, it will likely evolve to respond in a similar fashion to GDPR-related incidents.

By examining how the breach notification laws in the United States shaped the development of cyber insurance over the past two decades, we may be able to anticipate what the GDPR will mean for the cyber insurance market going forward, both in the EU and the United States.

The U.S. Cyber Insurance Market

In the United States, cyber insurance has developed considerably since it was first introduced to the market. While it has been available since the late 1990s to cover the anticipated catastrophic Y2K losses, it truly started growing in popularity in the early 2000s, when identity theft and mass data breaches became prevalent and various states began introducing data breach notification laws, many of which involved significant fines and penalties.

Over the years, cyber insurance policies in the United States have developed to provide fairly robust coverage for expenses associated with data breaches. While most policies will not cover the regulatory fines and penalties assessed against a company as a result of a data breach, they customarily cover numerous categories of related expenses, such as credit monitoring services, credit card re-issuing fees, investigation services and notification expenses. Another element of cyber insurance coverage is liability for third-party claims, which is extremely important in the era of class action suits in the aftermath of data breaches. Meanwhile, as data breach response and remediation became more and more expensive, cyber insurance products have also adapted to meet these needs.

Insurance professionals who sell cyber insurance report seeing a significant market shift over the past decade alone. Then, only a few products were available. Because there was little underwriting data on cyberrisks, the early policies contained many broad exclusions and non-standard conditions. The premiums were high while coverage was quite limited. Businesses had an aversion to purchasing cyber coverage, and only large companies and certain industries like online retail and health care bought cyber policies.

The market looks very different today. More than 100 carriers write cyber insurance, resulting in improved and more standardized policy language. Insurance premiums have decreased, while what is covered has increased significantly. Specific coverage has also emerged to address new threats such as cyber extortion response, decryption and data restoration. When a business buys cyber insurance today, it receives a full suite of services to help navigate a data breach incident. Clients from virtually every industry and line of business are asking for cyber coverage now, generally appearing to recognize that, if you are in business, you have risk.

Data Privacy in Europe

In stark contrast to the United States, European companies have little experience with a data breach regime marked by expensive notifications and potential lawsuits by individuals whose personal information was compromised. Until now, they largely have had nothing equivalent to U.S. data breach notification laws. Granted, the ePrivacy Regulation was introduced in 2009 for telecommunication companies and internet service providers, and European banks and insurance companies were subject to data protection rules, but this only affected a relatively small number of firms in certain sectors, so most businesses paid little attention.

In the EU, an alarming number of companies do not carry cyber insurance at all. According to a recent survey by SC Media, only 25% of U.K. firms carry dedicated cyber insurance. Similarly, in its Global Digital Small Business Insurance Survey, PwC polled 2,100 small businesses in 14 countries (including the U.K., Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Poland, France and Spain) and found that only 16% carried cyber insurance. Aon Inpoint’s Global Cyber Market Overview reported that the European standalone cyber market was estimated at $135 million in annual gross written premium in 2015. By contrast, the U.S. standalone cyber market was $1.5 billion.

Both the London market and individual EU insurers expected a surge in demand for cyber insurance once the GDPR went into effect. Inga Beale, the outgoing chief executive of Lloyd’s of London, estimated an increase in gross written premium for European cyber insurance to more than $2 billion annually by 2020, partly as a result of the GDPR. So far, however, customers have not rushed to buy. According to some sources, including a senior underwriter and product manager for Colonnade Insurance S.A. (which offers a GDPR-specific product for the Slovakia insurance market), while a few cyber policies have been sold, most clients are only making inquiries into pricing and leaving it at that.

What Will GDPR Mean for Cyber Insurance?

GDPR will likely affect the cyber insurance market both in the EU and in the United States. Once many U.S.-based companies realize that they are subject to the regulation, they will seek GDPR-tailored extensions of coverage for their existing cyber insurance policies. This, in turn, will mean that the carriers selling in the U.S. market will need to make changes to the cyber policies to accommodate the new demand. Because the U.S. cyber insurance market is quite competitive, we may see variations in GDPR-related policy wording and a multitude of different coverages available.

In the EU, there is tremendous growth potential for cyber insurance. Once the first enforcement action against a larger company for breach of GDPR makes headlines, many companies will likely scramble to find ways to protect themselves from GDPR-related liabilities. (While four suits were filed immediately after the regulation went into effect against Google’s Android, Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram alleging “forced consent” in violation of the GDPR, it remains to be seen how the EU data regulators will address them.) Nevertheless, it may take some time before EU businesses start buying cyber insurance to address this need because in many European markets, customers and insurance brokers are not familiar with cyber insurance and how it responds in the event of a claim. Indeed, a recent study surveying the U.K. cyber insurance market by Secure Systems Innovation Corporation listed “not understanding their own risk exposures” as one of the main reasons customers do not buy cyber insurance.

In theory, most cyber policies in the market already cover GDPR-liability arising out of a cyber breach or data security event as articles of the GDPR mirror data breach notification laws for which a cyber policy already provides coverage. With the attention that the GDPR has received over the past year, however, many of the cyber insurance carriers have developed affirmative or confirmatory coverage offered through GDPR-specific endorsements to address any doubts. There are, however, certain scenarios in which a company would not be covered, as a company may violate the GDPR in a way that does not trigger a cyber policy in the traditional sense—specifically, exposures involving collection, retention or processing of information.

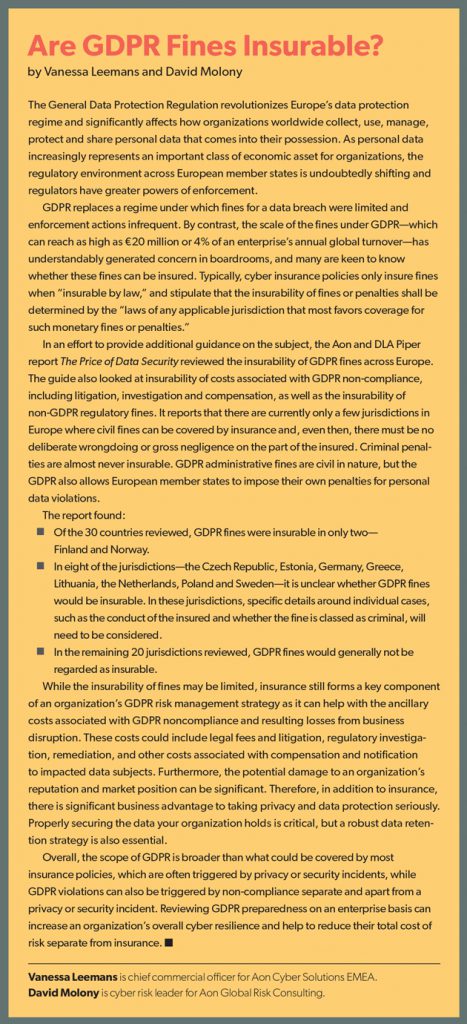

A big issue is whether the GDPR fines can be insured (see sidebar). In May, Aon and DLA Piper issued a guide examining this question for all European countries. While certain types of fines cannot be insured in almost any country, there is still a lot that a cyber insurance policy would cover in the event of a GDPR-related enforcement action, such as costs associated with an investigation, including potential legal and expert fees; compensation claims from individuals brought against a company as a result of non-compliance with the GDPR; and costs of repairing the damaged reputation in the wake of a publicized enforcement action. In any case, the potential uninsurability of the fines (arguably the highest potential exposure in the event of an enforcement action), or at least the present uncertainty as to whether the fines can be covered, may be a significant reason more companies are not turning to cyber insurance as a GDPR risk management tool. It is unlikely that European businesses are being lulled by a false sense of security that other lines of insurance provide coverage for a GDPR-related exposure, however. While certain losses related to a cyberattack or a data breach have historically been covered under general liability or property insurance policies (at least in the United States), GDPR-related risks are almost certainly not going to be captured under the wording of these other products.

A cyber insurance policy with specific coverage tailored to GDPR could be particularly valuable to address the risk of group privacy claims by affected individuals. The GDPR gives EU data subjects whose information has been compromised a right to claim compensation from responsible data controllers and processors. This right is broad, also capturing “non-material damage” such as distress and psychological harm. This could mean significant expense and reputation damage to European businesses faced with a consumer or employee group action.

It remains to be seen whether the EU insurance market is ready for a spike in demand caused by the GDPR. Several EU-based carriers have already developed new insurance products to provide coverage for GDPR-related expenses, offered either as stand-alone products or as an extension of more traditional cyber policy wording. These cover expenses related to failure to comply with the GDPR notification requirements and expenses associated with enforcement action by a regulator. Once market participants realize that this coverage is available, businesses may turn to cyber insurance with built-in GDPR coverage to manage this risk.

It will be interesting to see if the EU insurance market will look to how data breach notification laws and subsequent enforcement actions and lawsuits shaped the development cyber insurance coverage in the United States for guidance in transforming currently under-utilized cyber insurance products into a viable market in the EU. The similarities between the GDPR and U.S. data breach notification laws could help carriers that sell cyber insurance in the EU skip the growing pains the U.S. insurance market experienced and offer more sophisticated, tailored insurance products from the outset.