This post first appeared on IBM Business of Government. Read the original article.

Today, the generation of new ideas on “how” to undertake administrative reforms has outstripped the questions: “why” to reform and “when” to reform “what”?

Even before the policymakers have fully grasped the groundbreaking and innovative ideas of “new public management,” “re-inventing the government,” “agile government,” “data-driven government,” “citizen-centric government,” “connected government,” “e-government” and “smart government,” they find themselves debating the possibilities of “AI in government.” These are, no doubt, all good ideas and initiatives, but the deluge of these ideas on making the government work better, faster and cheaper has left the real-world policymakers and the experts confused and intellectually paralyzed.

To be sure, the apex policy policymakers responsible for administrative reforms, who are usually the heads of public service in their countries, are sincere and well-meaning public servants. In my experience, they are indeed the best and the brightest civil servants in their countries and want to do the very best in the limited time they have left in their tenure at the height of their civil service career. These apex policy makers are often under pressure to adopt the administrative reforms that happen to be the flavor of the moment.

Their attempts to reform the administrative machinery in their respective countries face another challenge. No matter what administrative reform measures the decision makers implement, it is difficult to convince everyone that the government is performing better because of these measures. This is primarily because even today the performance of the government organization in most countries lies in the eyes of the beholder.

Public administration reformers can learn a great deal from the way medical doctors treat their patients. When a sick patient is brought to a hospital, as the very first step, the attending nurse takes the vitals and hooks up the patient to various machines that monitor these vitals. All this is done well before the doctor steps into the room. Based on the data on vitals, the doctor decides the ailment and health of the patient before prescribing the necessary medicines. These vitals of the patient are then monitored regularly after giving the medicines prescribed by the doctor. If the medicines work, then the treatment continues till the patient is nurtured back to health. If not, the doctor reconsiders the prescribed medicines or their dosages. This change in medicine and/or dosage is entirely possible because of the system to measure the vitals of the patient.

Just like the medical doctors, when public administration experts are asked to prescribe medicines for a sick (non-performing) department, they should be able to first measure the health of the organization and then monitor its health continuously. This is where the problem lies. Unlike the medical doctor who takes a holistic view and can measure the vitals of the patient, the public administration experts do not have this ability as part of their standard operating procedure. Almost all doctors in almost all modern medical facilities have a similar protocol to judge the health of a human being. Again, unlike the medical profession, there is no consensus on how to measure the health (i.e. performance) of a government department. The result is, therefore, quite often very counterproductive. It is like giving antibiotics to a patient without determining whether the patient has viral or bacterial infection.

This is what we mean by a hierarchy of administrative reforms. Not all reforms are of equal importance. Some reforms are a “necessary” condition for all other reforms to succeed. These reforms relate primarily to the government’s ability to measure the health of a government entity. Therefore, if one does not have a rigorous and reliable system to monitor the health of a government department, then any medicine should suffice. We will never know whether that medicine improved or caused the health to worsen. That is precisely what is happening today around administrative reforms. The focus is on how good the medicine is seemingly and not whether it is appropriate or whether it is making any difference (positive or negative). Artificial Intelligence (AI) in government sounds better than Agile government and hence it is the flavor of the month.

The idea presented here is neither new nor pathbreaking. The following exchange from the Alice in Wonderland summarizes the point well:

Alice: “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

The Cheshire Cat: “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”

Alice: “I don’t much care where –”

The Cheshire Cat: “Then it doesn’t matter which way you go.”

Likewise, if the goals are not clear, any reform will do. Only when a government department knows its desired destination then, only then, can they figure out whether a particular administrative reform will help them move in their desired direction faster, better, and in a less costly manner.

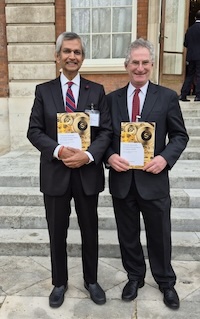

The Commonwealth Secretariat has followed this strategy toward the hierarchy of administrative reforms. In the Commonwealth Heads of Public Service Meeting in 2022 all 56 countries of the Commonwealth, representing 2.5 billion people, agreed to a common approach to measuring the health of a government department and these principles were adopted as the Generally Accepted Performance Principles (GAPP).

In the forthcoming Commonwealth Heads of Public Service Meeting in London on April 22-24, 2024, the focus will now shift to the second order reforms. There will be a discussion on SMART Government (as well as AI in Government and a presentation co-led by Dan Chenok about the IBM Center for The Business of Government’s partnership with the Commonwealth Hub for The Business of Government). I believe that is the correct way to proceed – first you decide how you measure the vitals and then you prescribe the medicine to treat.