This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the first ransomware attack, a 1989 virus called the AIDS Trojan that targeted AIDS researchers. While the strategy went largely unused for some time, ransomware has surged over the past several years, becoming one of the most well-known threats in cyberrisk today. This year saw a notable increase in ransomware activity specifically among public entities, as a number of cities found themselves in the crosshairs of cybercriminals. The lessons learned from these attacks can help risk managers in understand the resulting risks and prepare for future threats.

Across the United States, cities are grappling with the risk of ransomware, a type of malware that encrypts an entity’s data, allowing attackers to extort the victim for payment via cryptocurrency by threatening to release or destroy the data and incapacitating operations. By the beginning of November, cybersecurity company Barracuda reported that more than 70 U.S. cities had been the victims of ransomware attacks in 2019, the majority of which have less than 50,000 residents. StateScoop, a technology and government-focused media outlet, estimated the number to be even higher at 99. Municipalities are being targeted with growing frequency because of their fairly weak IT security practices, as well as the outsized attention and urgency that shutting down cities’ systems can elicit. Additionally, cities often have limited budgets and technical staff, and may not have insurance to cover the attacks, leaving them exposed to exorbitant ransom or recovery costs.

In one of the first high-profile attacks on a major city, the government of Atlanta was hit with a ransomware attack in March 2018 that crippled the city’s computer systems, forcing administrative offices to conduct business by pen and paper or even shutter altogether. The hacker or hackers asked the city to pay around $52,000 in bitcoin, but the city refused, leaving it scrambling to restore and protect its systems. Over a year later, that process has not yet fully ended. Atlanta officials have estimated that the recovery and cost of lost business could exceed $17 million.

Similarly, Baltimore suffered a ransomware attack in May 2019, with the hackers reportedly demanding 13 bitcoins (around $76,000 at the time) and shutting down many of the city’s essential systems. Baltimore’s government also refused to pay, opting to rebuild its computer systems instead. Its budget office has estimated that the city will have to pay at least $18.2 million over the course of recovery, factoring in both direct costs and lost revenue.

And in August, 22 small towns in Texas were reportedly targeted in a coordinated ransomware scheme, with the attacker demanding a collective ransom of $2.5 million, according to the mayor of Keane (one of the towns affected). A spokesperson for the Texas Department of Information Resources said that he was unaware of any of the towns paying the requested ransoms, and it has not been revealed if any data was permanently lost.

Responding to Ransomware

Municipalities and other entities hit with ransomware face a dilemma. They can either pay the ransoms and hopefully recover data and restore operations quickly, or they can undertake the often-laborious process of recovering files from backups or investigating the type of ransomware and attempting to decrypt the hijacked files by themselves or with help from IT contractors. Since the recovery process can take longer—sometimes even weeks or months—many victims opt for paying the ransom, despite the risk of the attacker reneging on the promise to decrypt the captured data. Some insurance companies covering losses from ransomware incidents have reportedly advocated paying the ransom, cutting probable recovery time and allowing them to pay out a smaller sum than if they had to cover lost revenue from a longer business interruption.

However, the FBI recommends against victims paying attackers because it does not guarantee the return of their data and may encourage more crime. According to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center, “Paying ransoms emboldens criminals to target other organizations and provides an alluring and lucrative enterprise to other criminals.” Cybersecurity firm Recorded Future reported that only around 17% of affected cities pay ransoms. In July, the U.S. Conference of Mayors, which represents mayors of cities with populations over 30,000, passed a resolution sponsored by Baltimore’s mayor opposing payment to ransomware attackers, which stated that municipalities have “a vested interest in de-incentivizing these attacks to prevent further harm.”

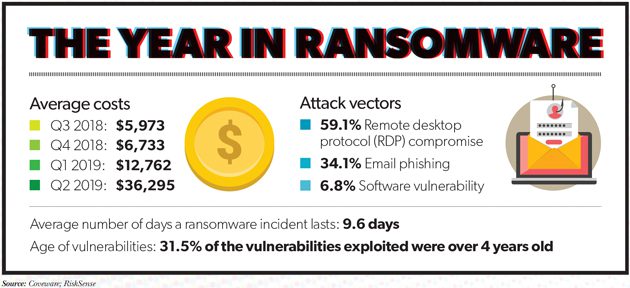

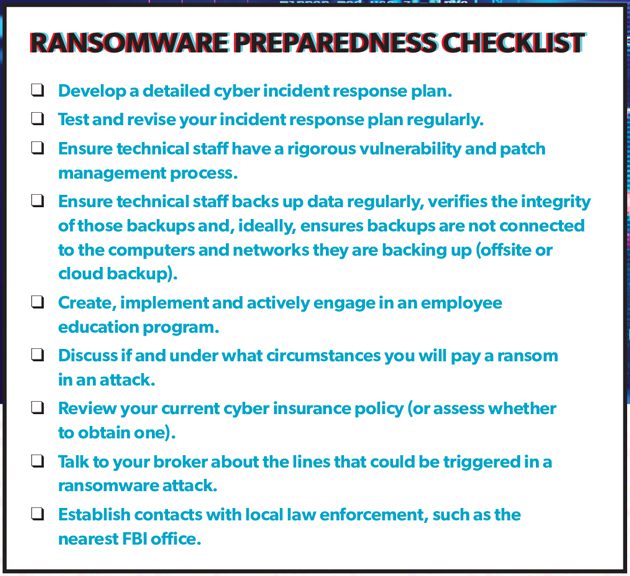

The best way to avoid becoming the victim of ransomware is to invest in IT security before an incident occurs, particularly by patching vulnerabilities and updating systems regularly. Cybersecurity company RiskSense examined 57 vulnerabilities that hackers exploited to infect systems with ransomware and found that 31.5% were unpatched vulnerabilities from 2015 or earlier, with some even dating back as far as 2010. Audits of Atlanta’s computer systems before it was attacked showed thousands of potential vulnerabilities, including outdated software and a lax update policy that was habitually ignored.

Ensuring that the organization is thoroughly backing up its data also allows it to restore systems more quickly if compromised. These backups should be tested and updated often, while also making sure that they are not connected to the systems they are backing up by storing them elsewhere, including in the cloud or offline. Baltimore reportedly hosted its email almost entirely on an internal server before its systems were infected, and the city’s IT department stored its data locally without backing any of it up. This made it easier for attackers to encrypt the city’s system and may have led to permanent data loss.

A disaster recovery and business continuity plan is also an essential part of any organization’s preparations for a ransomware attack. Knowing in advance who should handle specific parts of cyberattack response, such as isolating the affected systems or contacting law enforcement, can speed recovery efforts, whether the organization decides to pay the ransom or not. Establishing relationships and partnerships with the organization’s insurer, internal and external cybersecurity personnel, and other essential stakeholders before an incident occurs will save the organization time and money in the event of an attack.

In addition to strengthening their IT systems, creating and enacting a recovery plan and choosing the right cyber insurance policy, organizations must ensure that they adequately train and test their staff to recognize phishing emails and messages that may contain malicious links or attachments. According to Coveware, 34.1% of ransomware cases in the second quarter of 2019 were the result of email phishing. No matter how strong security is, just one employee mistakenly clicking the wrong thing can allow attackers to cripple the whole enterprise.

Insurance Implications

Coveware reported that, in the second quarter of 2019, the average ransom payment for all enterprises hit $36,295, a notable increase from the first-quarter average of $12,762. This was even more dramatic in the public sector, however, where victims paid an average ransom of $338,700—almost 10 times the global enterprise average.

More public entities are looking at cyber insurance options as the primary risk transfer option to defray these costs. The Wall Street Journal reported last year that a majority of the country’s 25 most populous cities either had or were considering cyber insurance policies. As this year has demonstrated, such considerations are far from limited to the largest municipalities.

When Florida’s Lake City and Riviera Beach fell victims to ransomware attacks this year, city leaders specifically noted their cyber insurance policies as a key factor in making the controversial decision to pay the ransoms. Both cities had policies that would pay the majority of the ransoms demanded—approximately $460,000 and $600,000, respectively—aside from a $10,000 deductible. Given the interruption of critical services and the costs of forensics and recovery efforts, officials felt that it was both faster and more cost-effective to pay the attackers for a decryption key.

“We pay a $10,000 deductible, and we get back to business, hopefully. Or we go, ‘No, we’re not going to do that,’ then we spend money we don’t have to just get back up and running,” Lake City Mayor Stephen Witt later told ProPublica. “And so to me, it wasn’t a pleasant decision, but it was the only decision.”

After a ransomware attack hit LaPorte County, Illinois, in July, FBI negotiators brought in during the incident response process were reportedly able to negotiate a lower ransom than initially demanded. Officials then elected to pay a $130,000 ransom, of which county commissioners said $100,000 was set to be paid through an insurance policy with Travelers.

These decisions may have been informed, in part, by Baltimore still being mired in disruption from its attack, which struck just the month before. In October, the city purchased its own cyber insurance policy for the first time. In fact, it purchased two. After Baltimore’s risk management office reviewed bids from 17 carriers, the city purchased policies with Chubb and AXA XL, each for $10 million in liability coverage after a $1 million deductible, for a total $835,000 in premiums. The policies are supposed to cover incident response, business interruption and ransom payments.

“As the world changes and as criminal acts change, you have to adjust,” City Council President Brandon Scott told the Wall Street Journal. “This is an adjustment well worth it to protect the citizens of Baltimore and, most importantly, protect their taxpayer dollars in the event this happens again.”

Public entity risk managers may need to be aware not only of the reputation risk associated with their crisis response and ransom payment decisions, but also potential questions about their risk mitigation and transfer decisions like purchasing cyber coverage.

Not all may come down in favor of purchasing, however. The cases in Florida this year sparked considerable debate not only about the moral and practical questions of whether to pay a ransom, but of the insurance industry’s role in the spate of ransomware attacks. Cases against public entities, by their very nature, require a different level of disclosure than is common in the private sector and draw considerable public attention—as do the ransoms insurers may cover. Many have argued that insurers’ responses may be fueling the surge in attacks, and some experts in the cybersecurity industry and public sector have attempted to correlate the public payments to the rising ransom demands seen over the course of the year. Moving forward, public entity risk managers may need to be aware not only of the reputation risk associated with their crisis response and ransom payment decisions, but also potential questions about their risk mitigation and transfer decisions like purchasing cyber coverage.

The market itself will likely feel the effect of these payouts moving forward. As with most lines seeing an uptick in claims, it is reasonable to expect that public entities may see steeper rates for cyber insurance coverage or, at a minimum, increasing retentions. Both of the policies Baltimore recently purchased, for example, have a $1 million deductible. There remains enough capacity in the market and competition among cyber insurers, however, to help moderate potential rate increases.

Robert Parisi, managing director and cyber product leader at Marsh, told Business Insurance in July that the past 10 to 15 years have demonstrated the cyber insurance market’s capacity to absorb some very large loss events, so he did not necessarily expect a sharp increase in rates in the near future. However, he added, “I think you will see carriers certainly ask more questions around whatever the latest issues were with regard to municipalities’ ransomware. It’s become a fairly common point of inquiry now across all industries, including municipalities.”

Going forward, insurers will undoubtedly be taking a closer look at what technology infrastructure and cyberrisk management measures municipalities have in place. Heightened scrutiny from underwriters should underscore the importance of public entity risk managers focusing proactively on everything from detailed contingency planning to security awareness training for staff (see sidebar).

Other Public Entity Threats on the Horizon

Aside from municipalities, other public sector enterprises have endured more ransomware attacks this year or have been specifically put on notice about the threat, particularly education and healthcare entities. School systems and hospitals have been attacked throughout the year, crippling critical services and introducing acute concern about the security of key classes of protected data—personal information regarding children and personal health information. Advocacy groups in these sectors have turned greater attention to these issues, attempting outreach, education and preparation efforts among their stakeholders.

Worldwide, security and insurance experts have also increased their warnings about the potential peril to other key kinds of public entities like ports, where public entities’ risk management poses particularly massive risk to both the public and private sectors. As the NotPetya attack demonstrated, the business interruption risks from attacks that hit the shipping industry and cripple ports can be particularly severe across the supply chain. A recent report produced by the University of Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies, Lloyd’s and others found that a worst-case scenario attack on major Asia-Pacific ports could cause up to $110 billion in damages, for example, and given insurance penetration rates and the uncertainties inherent in non-affirmative or “silent” cyber coverage, 92% of the economic costs could be uninsured. Approximately 60% of losses would be due to business interruption or contingent business interruption, non-affirmative cyber represented up to 57% of losses, and economic losses could spread throughout the supply chain. Indeed, businesses along the supply chain faced 21% of claims in the scenario.

As the year closes, ransomware attacks show no sign of slowing. Rather, as these attacks continue to provide effective paydays for financially motivated criminals and the disruption or outright chaos other threat actors seek, public sector risk managers must refine their cyberattack prevention and response measures to prepare their organizations for tomorrow’s threats.