This post first appeared on Risk Management Monitor. Read the original article.

Last week, after already experiencing heavy rainfalls and flooding, New Orleans was preparing for tropical storm Barry, expecting the storm to overflow or even breach the city’s levees. Flights in and out of the city were cancelled, as were concerts and other public events, as the city braced for catastrophe. Barry ended up narrowly missing New Orleans, and instead moved inland, drenching other parts of Louisiana and Mississippi and causing floods and mass power outages in those areas. It was yet another example of how major flooding has become a normal occurrence for many regions of the country, and by all indications, it is becoming worse each year.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) stated in its report 2017 State of U.S. High Tide Flooding and 2018 Outlook that “The projected increase in high tide flooding in 2018 may be as much as 60 percent higher across U.S. coastlines as compared to typical flooding about 20 years ago and 100% higher than 30 years ago.” This prediction turned out to be accurate, as the United States saw massive flooding throughout 2018, including “sunny-day” or “high-tide” flooding that occurs during high tides outside of hurricane events.

In its recent report on 2018 high-tide flooding and 2019 outlook, the NOAA said that these floods’ median frequency in 2018 “reached 5 days, which tied the historical record of 2015.” Of the 98 observed locations along the U.S. coastline, 12 reportedly broke or tied their all-time records for high-tide flooding in 2018. And now, the NOAA is predicting that 2019 could be even worse.

The NOAA noted that high-tide flooding “is increasingly common due to years of relative sea level increases. It no longer takes a strong storm or a hurricane to cause flooding in many coastal areas.” The Union of Concerned Scientists has said that sea level rise is accelerating, that “sea levels in the U.S. are rising fastest along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico,” and that the primary reason for this sea level rise is climate change melting land ice and heating oceans.

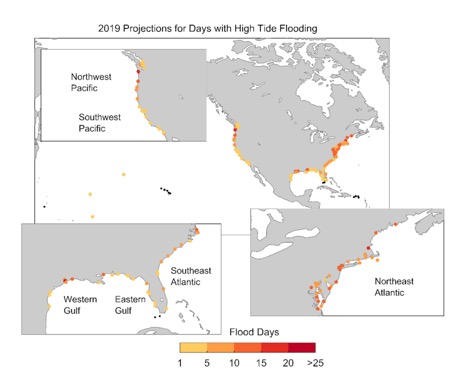

According to the NOAA’s 2019 projections, it expects high-tide flooding along the U.S. coastlines this year to reach double the numbers from 2000. Additionally, “the Northeast Atlantic could see a 140% increase, the Southeast could see a 190% increase, and the Western Gulf of Mexico could see a 130% increase.”

Almost 40% of the U.S. population lives in coastal areas, and could be at risk from flooding effects. With the start of hurricane season, these dangers will only increase as storms batter the coasts. Even before Barry threatened, New Orleans faced massive flooding last week, while Pittsburgh contended with flash floods. And the week before, heavy rains left Washington, D.C. and surrounding towns swimming in water that overwhelmed the city’s storm water pipes.

These increasing floods mean serious losses for people, municipalities and businesses. The recent DC-area floods reportedly caused $3.5 million in damage to Arlington, Virginia county infrastructure alone. In March, a “bomb cyclone” hit Nebraska, with heavy rainfall causing damages totaling more than $1.3 billion. This figure includes $449 million in road, levee and other infrastructure damage, as well as serious damage to more than 2,000 homes and 340 businesses. Iowa also experienced flooding that caused water treatment plants to shut down, depriving two cities’ residents of fresh water. And across the Midwest, agriculture was also hit hard by flooding, slowing corn and soybean planting. The delay may decrease harvests by at least 8% and increase prices worldwide.

As Risk Management Monitor has previously reported, Texas A&M University at Galveston and the Texas General Land Office examined the 50-year impact of a major storm hitting Galveston Bay on the Texas coast near Houston, finding that major storm events that caused flooding would have huge secondary effects on the economy, both locally and nationally.

Various states, including those along the Mississippi River, have already enacted flood control measures like levees, dams and flood walls, but have seen this year’s increased flooding defeat these measures. Others have encouraged residents to purchase flood insurance to offset losses. But the increasing scope of future floods may mean that these steps are not enough. Though tropical storm Barry missed New Orleans, experts have still expressed concern about coming storms possibly “topping” the city’s levees, which could cause even more damage to the already-flooded city.