This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

In March, the U.S. Department of Justice charged 50 people in a long-running bribery and fraud operation designed to help students gain admission into 11 of the country’s top colleges and universities. The scheme involved more than 30 parents, including Hollywood actresses and prominent business leaders, who allegedly conspired to bribe school officials and coaches, cheat on college entrance exams, and falsify athletic credentials to buy their children’s way into these top-tier schools.

The scandal was yet another example of the wide range of issues that can affect the reputation and bottom line of colleges and universities. Point shaving and sexual misconduct scandals have plagued athletic departments. Falsified or flawed research results, stolen research and cheating have marred academic departments. Embezzlement schemes have surfaced in administrative departments.

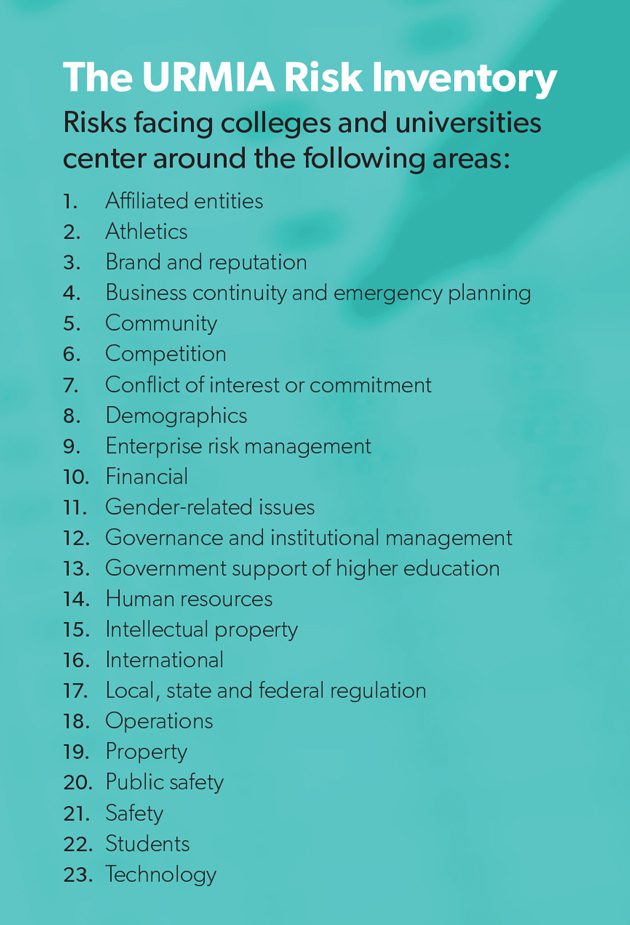

Amid it all, risk management departments must find a way to address this laundry list of risks while working in a heavily-siloed environment that often does not share policies and practices across the organization. Given the broad structure of colleges and universities, it is not difficult to see the problem. Currently, the University Risk Management and Insurance Association’s (URMIA) Risk Inventory organizes the areas of risk faced by higher education institutions into 23 separate groups (see sidebar). Within each risk group, there are compliance, operational, reporting, strategic and reputational risks, and within those categories fall some 290 identified risk areas.

While the URMIA list provides a general guideline for potential risk exposures, no two schools will have the same experience. “Each institution is unique, and the potential for issues to arise is more related to internal dynamics,” said Luke Figora, senior associate vice president and chief risk and compliance officer at Northwestern University and president of URMIA.

Compounded by the rapid evolution of risks, organizations can easily be caught off guard. Because institutions focus on traditional minimization and mitigation strategies, they are not always able to adapt quickly enough to stay ahead of the issues. “As the recent news has shown, some institutions have identified areas of significant risk, but haven’t done an effective job at handling those situations and preventing them from getting worse,” Figora said. “Those compound errors that we’ve traditionally suffered from need to be removed from our future models.”

The media attention surrounding the admissions scandal has highlighted a key risk exposure from areas that have traditionally operated autonomously and seemed immune from oversight, such as influential or high-profile athletic, admissions and research departments. “It’s notable to me that these are typically areas that hold internal institutional power,” Figora said. “Some might call them ‘sacred cows.’” Such autonomy separates departments, faculty and staff from any centralized approach to risk, making it difficult for any traditional risk management approach to improve accountability.

The media attention surrounding the admissions scandal has highlighted a key risk exposure from areas that have traditionally operated autonomously and seemed immune from oversight, such as influential or high-profile athletic, admissions and research departments. “It’s notable to me that these are typically areas that hold internal institutional power,” Figora said. “Some might call them ‘sacred cows.’” Such autonomy separates departments, faculty and staff from any centralized approach to risk, making it difficult for any traditional risk management approach to improve accountability.

Economic pressures further increase that difficulty. According to Adrienne Larmett, senior manager in the risk and internal audit practice at Baker Tilly, institutions are competing more intensely than ever for a shrinking pool of students. The overall population of traditional college-aged students peaked in 2012 and since then, their enrollment continues to decline. “There is increased competition for colleges and universities to go after this type of student, which—if we think about it from a motivation standpoint—is how any type of fraud or misreporting can happen,” she said.

Overcoming Risk Management Barriers

Figora believes that, because of the complexity and decentralized nature of higher education, there is an uneven understanding of risks, policies and expectations throughout the organization. Yet even when a centralized risk approach is implemented, he said the nature of campus culture can make it difficult to control every situation and achieve the desired results.

According to Sean Murphy, managing director of BDO USA’s crisis management, business continuity and third-party risk operations, culture is a root cause of risk and is not being addressed on many college campuses. Part of the problem may be that the standard risk management approach—using statistical analysis and insurance solutions—is not effective for risks that are more behavioral in nature, like fraud and bribery. “It’s behavioral in that it deals with culture, it deals with reputation,” he said.

Murphy advocates for enterprise risk management (ERM) strategies within higher education, but without addressing the cultural issues, such strategies will not be effective. Changing behaviors is an enterprise-wide issue that all executives, board members and risk managers should be addressing.

That starts with understanding human nature. Risk management can identify potential behavioral issues if they know what to look for. “We know that if you have a large amount of credit card debt, that directly correlates to fraud,” Murphy said. “The more debt you have, the more you skimp on your expenses. So you know right away, from an organizational perspective, if you have staff with high debt, they are highly susceptible to doing bad things.”

That also includes not speaking up after witnessing fraud or other behavioral issues. Murphy says affiliation bias—the bias that occurs when evaluating another person’s actions based on their connection to an organization rather than on the behavior itself—deters people from coming forward and is another troubling cultural problem.

So while implementing a standard ERM plan is a step in the right direction, it is not enough. “The problem with ERM today is [risk managers] get in a room and put all these risks on a map, and they prioritize them,” Murphy said. “But to be able execute on them and be able to change, that’s a whole different ball game. We have to realize that the era of plans is really limited in its capabilities for today’s world.”

ERM plans need to address just how wildly higher education risks have evolved and include a way to measure motive and behavioral influences. They should also include ways to address the siloed nature and independent actions of administrators, faculty and staff. Risk managers should take a step back and view the enterprise broadly, not just within each department. “Work across everything and start to put together what the institution’s unique risk universe looks like,” Larmett said.

ERM plans need to address just how wildly higher education risks have evolved and include a way to measure motive and behavioral influences.

From there, risk management can start examining potential cultural issues. Larmett suggests working with the compliance and internal audit departments to examine the institution’s risk profile. “What’s the culture of the institution that would allow something like fraud to occur? Do we have a culture that would facilitate someone being able to raise their hand and say ‘I know something is going on here’?”

Risk management should also focus on strengthening investigation and reporting policies. Behavioral risks often go unreported because there is no reporting process in place, or because the process has not been communicated effectively. “The challenge to universities is they are made up of a number of departments and silos, and I think the key for risk managers is to break down those silos,” said Eric Pan, area president and managing director of the higher education practice at Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. “Any risk happening in those departments has a reporting mechanism to a centralized site.”

It is risk management’s responsibility to communicate that reporting process throughout the organization and underline its importance. “Having a proper investigation process and making sure incidents are reported to the insurance company and to law enforcement on a timely basis are critical,” Pan said. “In all the mega-verdicts you read about, I believe many have a breakdown in reporting and early treatment of the risk once the incident was raised.”

Part of the reason for such a breakdown is a lack of formalized and documented policies. Too many institutions have operated with the same protocol for far too long, so when events occur, they are running to catch up. “Sadly, there’s not always an opportunity to be proactive, so it’s when there are adverse events, like admissions scandals, we now have to do a lot of work to put those controls in and monitor them,” Larmett said.

Crisis and Opportunity

Even with stronger reporting policies and checks and balances, problems will still occur. Therefore, it is also important to have public relations and crisis management policies in place. Pan recommended testing each policy and response plan during tabletop exercises, and engaging public relations consultants, who can teach internal teams how to communicate with the media, speak with stakeholders and respond to the community.

According to Murphy, it is important to control the narrative. “There are only three actors in a crisis—there’s a victim, a villain and a hero. You have to think of these reputational risk crises like this,” he said.

The goal is to transform the institution into the hero. But without a plan, that will not happen. Unfortunately, too many schools are unwilling to address a breaking issue. “That’s a bad way of looking at it,” Murphy said. “People are going to remember for a very long time, even if it’s false. If you don’t address it and it’s false, what happens then is confirmation bias—people start believing it’s true and it is very hard to change their minds.”

He believes that a crisis actually presents an opportunity to move forward. “It’s the number-one time people are paying attention, so it’s your number-one time to earn brand equity. That’s one of the few times you can make instrumental change to an organization.”

Of course, change can also be proactive. Schools like Northwestern have already revamped their risk framework to address emerging issues. The university has redesigned its investigation protocol and focused on handling issues that could involve senior-level officers or more complex concerns. “We have also spent time building a crisis communications framework tied to some of our specific risks so we aren’t scrambling to do that in real-time,” Figora said. Northwestern has also trained staff and faculty on what issues should be escalated centrally, and when the department can deal with something internally. “We want to make sure important things are being handled appropriately and immediately,” he explained.

Given the breadth of risks facing higher education and to help spur wider change, risk managers should not only be monitoring national issues like fraud, sexual harassment and discrimination, but also taking steps to understand their institution’s strategic goals and mission, as well as what competing interests are at play. Far too often, higher education risk managers only address insurance or minimizing liability when the conversation should be broader.

“I find it helpful to reinforce to our leaders that I am here to help them meet their goals and reduce the risks to them having success,” Figora said. “Part of this is also about protecting them from issues that could catch them flat-footed—let me help you think about where problems might be hidden, and what we can do to close the gaps.”