This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

In April, federal authorities charged Rochester Drug Cooperative and two of its former executives with unlawfully distributing oxycodone and fentanyl and conspiring to defraud the Drug Enforcement Administration, fueling the opioid epidemic in the United States. While not a household name, RDC is one of the 10 largest drug wholesalers in the country, selling to over 1,300 pharmacies and netting over $1 billion in annual revenue. The indictment marked the first case in which federal prosecutors fighting the opioid crisis charged a major pharmaceutical distributor and individual executives with the same kind of felony drug-trafficking crimes as street dealers and cartels.

Prosecutors charged RDC as a corporate entity with conspiracy to distribute drugs, conspiracy to defraud the United States, and failure to file suspicious order reports, and the distributor has signed an agreement and consent decree “stipulating to the accuracy” of the charges. The company agreed to pay a $20 million fine, reform and enhance its Controlled Substances Act compliance program, and submit to supervision by an independent monitor for five years in exchange for deferring prosecution.

Concluding a two-year DEA probe, the escalation to filing criminal charges hinges on the state’s allegations that executives knew the opioid medications they distributed were ultimately being distributed illegally, in large part evidenced by the blatant failures in and disregard for the firm’s compliance program. Indeed, of the two RDC executives indicted, William Pietruszewski, the company’s former chief compliance officer, was personally charged with conspiring to distribute drugs, defrauding the government and failing to file reports to authorities about suspicious orders for controlled substances. He is reportedly cooperating with prosecutors and pleaded guilty and now faces a mandatory minimum 10-year sentence. Former CEO Laurence F. Doud III was also indicted and pleaded not guilty. If convicted, he faces a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years or a maximum of life in prison.

The RDC case paints a detailed illustration of a failed compliance program with dangerous results for the business, its executives and a nation ravaged by the drugs supplied. According to court filings, RDC identified over 8,300 “orders of interest” (an unusually high order for a particular drug) but failed to investigate them or alert the DEA, filing just four suspicious order reports from 2012 through 2016.

According to the Department of Justice, key red flags the company noted but ignored include: “dispensing highly abused controlled substances in large quantities; dispensing primarily controlled substances; dispensing quantities of controlled substances in amounts consistently higher than accepted medical standards; accepting a high percentage of cash for controlled substance prescriptions; dispensing to out-of-state patients; and filling controlled substances prescriptions issued by practitioners acting outside the scope of their medical practice, under investigation by law enforcement, or on RDC’s ‘watch list.’”

In fact, Doud and other senior management directed the compliance department—including Pietruszewski—not to report customers, even those characterized by employees as a “DEA investigation in the making” or “like a stick of dynamite waiting for [the] DEA to light the fuse.” RDC also distributed drugs to pharmacies that other distributors had cut off for suspicious activity, with Doud even instructing a compliance officer to visit such a prospective client, saying, “we are a knight in shining armor for independents.” Between 2012 and 2016, court filings report RDC’s sales of oxycodone rose from 4.7 million pills to 42.2 million (800%) and fentanyl sales rose from 63,000 doses to 1.3 million (2,000%). In the process, Doud’s compensation increased 125%.

The case should serve as a reminder to players in the pharmaceutical industry “of their role as gatekeepers of prescription medication,” according to DEA Special Agent in Charge Ray Donavan, who particularly emphasized the tie between rigorous compliance programs and the escalation to criminal charges. “The distribution of life-saving medication is paramount to public health; similarly, so is identifying rogue members of the pharmaceutical and medical fields whose diversion contributes to the record-breaking drug overdoses in America,” he said. “DEA investigates DEA registrants who divert controlled pharmaceutical medication into the wrong hands for the wrong reason. This historic investigation unveiled a criminal element of denial in RDC’s compliance practices, and holds them accountable for their egregious non-compliance according to the law.”

Turning to the Courts to Stem Crisis Costs

Across the United States, the magnitude of the opioid crisis continues to grow. According to the most recent data from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, overdose deaths hit a new high of over 70,000 in 2017, with 47,600 (or 67.8%) specifically involving opioids, a 12% increase from 2016. The National Safety Council’s analysis of preventable injuries and fatalities from the same year found that, for the first time, the odds of accidentally dying from an opioid overdose (1 in 96) are now greater than those of dying in a motor vehicle accident (1 in 103), and the lifetime odds of death from overdose are greater than the risk of fatal falls, pedestrian accidents, drownings and fires.

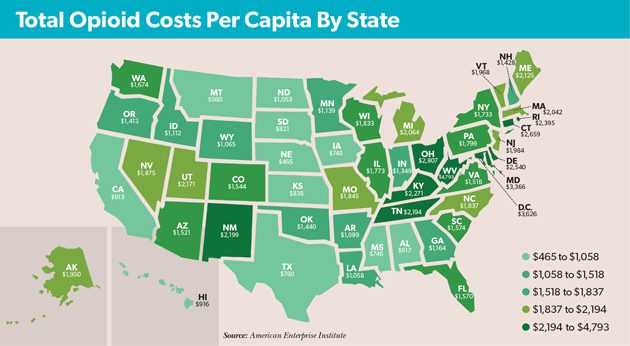

Direct costs have naturally increased as overdoses have spiked, putting significant strain on many state and local entities. According to research released last year by the American Enterprise Institute, the total costs of the crisis—including both direct costs and the economic impact—top $1,000 per capita in all but 11 states (see map). With the highest rate of annual opioid-related deaths, West Virginia’s total has surged to $4,793 per capita—approximately 12% of the state’s overall gross domestic product.

Mounting costs for state and local authorities run the gamut from health care and social services to labor force participation and GDP. In testimony before the Senate Banking Committee in 2017, then-Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen directly linked the crisis to declining labor-force participation among “prime-age workers.” While she noted it is unclear which is the symptom and which is the cause, Yellen made clear that the crisis had reached such a significant level that the productivity and economic impacts will last for years to come. Indeed, according to a recent study from researchers at Penn State, the opioid epidemic may have cost federal and state governments $37.8 billion purely in lost tax revenue due to opioid-related under- and unemployment alone.

Mounting costs for state and local authorities run the gamut from health care and social services to labor force participation and GDP. In testimony before the Senate Banking Committee in 2017, then-Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen directly linked the crisis to declining labor-force participation among “prime-age workers.” While she noted it is unclear which is the symptom and which is the cause, Yellen made clear that the crisis had reached such a significant level that the productivity and economic impacts will last for years to come. Indeed, according to a recent study from researchers at Penn State, the opioid epidemic may have cost federal and state governments $37.8 billion purely in lost tax revenue due to opioid-related under- and unemployment alone.

Against this backdrop, authorities are taking a new tack, taking aim directly at major players in the pharmaceutical industry to both better control the supply of drugs entering the market and recoup some of the costs of the crisis. In addition to broader malfeasance like deceptive marketing, prosecutors are shining a spotlight on personal greed among individual directors and officers as a primary factor fueling nationwide abuse of opiates. Striking far closer to home, holding executives personally accountable may prove a more compelling incentive for drug companies to meaningfully respond to the crisis and assert control over the production, distribution and marketing of opioids.

Lawsuits against major pharmaceutical companies involved in manufacturing and distributing opioids over the past two years have recently surged, causing increasingly large and numerous financial losses. As of May 17, at least 40 states have sued companies involved in manufacturing, distributing or dispensing opioids.

In March, OxyContin manufacturer Purdue Pharma agreed to pay $270 million to settle a lawsuit brought by the state of Oklahoma. The settlement came just days before the case was scheduled to be the first to litigate the industry’s role in the opioid epidemic before a jury. Over $100 million will be used to establish a national addiction treatment and research center at Oklahoma State University. The company will pay an additional $15 million annually and provide $20 million worth of addiction treatment and opioid rescue medications to the center over the next five years.

The Sackler family, which owns Purdue as a privately-held company, agreed to pay $75 million for the treatment and research center over the next five years. This is hardly the end of the consequences they personally face for their corporate governance activities. Eight members of the Sackler family have served on the board or as company executives, directing much of the strategy around the sales and marketing of OxyContin. According to a lawsuit filed by the Massachusetts attorney general in February, as the crisis has raged, Purdue paid members of the Sackler family more than $4 billion between 2008 and 2016. Arguing that the family has used deceptive marketing and aggressive sales strategies to disseminate addictive, lethal drugs and making a fortune off devastating addictions, suits just against the family have become innumerable. In Ohio, there are 1,600 consolidated suits against the Sacklers, while a federal suit filed in March by more than 600 cities, counties and Native American tribes across 28 states targets them for allegedly creating the crisis by deceptively marketing addictive and fatal drugs.

As the crisis continues to ravage communities across the country, prosecutors and citizens alike appear increasingly willing and eager to hold pharmaceutical companies and their individual leaders accountable. In May, billionaire John Kapoor, ex-CEO of major opioid manufacturer Insys Therapeutics, became the first executive convicted of racketeering in the recent wave of opioid-related litigation. Now facing up to 20 years in prison, Kapoor and four other former company executives were found guilty of defrauding insurance companies and bribing doctors to prescribe Subsys, a fentanyl-based spray initially approved for terminally ill cancer patients that was ultimately widely prescribed for other conditions involving chronic pain. A synthetic opioid 80 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, increasing consumption of fentanyl has spurred much of the increase in fatal opioid overdoses, particularly as many drug users do not realize heroin is often laced with fentanyl. Another of the company’s former CEOs, Michael Babich, pleaded guilty in January and became a witness for the prosecution. The scheme involved paying doctors to participate in fake events and treating them to lavish outings at strip clubs and restaurants Kapoor owned.

While hardly isolated cases, these are likely still just the tip of the iceberg. Federal authorities are encouraging the push by state and local authorities to seek relief from the pharmaceutical industry, aiding in the many fights to hold players in the industry directly responsible for fueling the crisis. To that end, last February, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the Prescription Interdiction and Litigation (PIL) Task Force, charged with supporting local jurisdictions in opioid-related lawsuits against prescription drug makers and distributors.

When announcing the charges in the RDC case, Geoffrey S. Berman, the United States attorney for the Southern District of New York, explicitly expressed the increasing shift by prosecutors toward holding directors and officers criminally culpable in a way that corporate executives simply have not faced to date. His office, he vowed, will “do everything in its power to combat this epidemic, from street-level dealers to the executives who illegally distribute drugs from their board rooms.”