This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

In the World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Risks Report, environmental and technological risks dominate the worldwide threat landscape. Of the 1,000 business, government and civil society leaders surveyed, most believe that global risks will only worsen in 2018, with 59% predicting an intensification of risks and only 7% predicting reduction. The top risks for the next 10 years are notably fundamental threats to the underlying structure of society, fueled by the “accelerating pace of change” and increasing interconnectivity. The potential outcomes range from catastrophic natural disasters to extinction-level rates of biodiversity loss to mounting concern about the possibility of new wars.

“Humanity has become remarkably adept at understanding how to mitigate conventional risks that can be relatively easily isolated and managed with standard risk management approaches,” the WEF explained. “But we are much less competent when it comes to dealing with complex risks in the interconnected systems that underpin our world, such as organizations, economies, societies and the environment. There are signs of strain in many of these systems: our accelerating pace of change is testing the absorptive capacities of institutions, communities and individuals.”

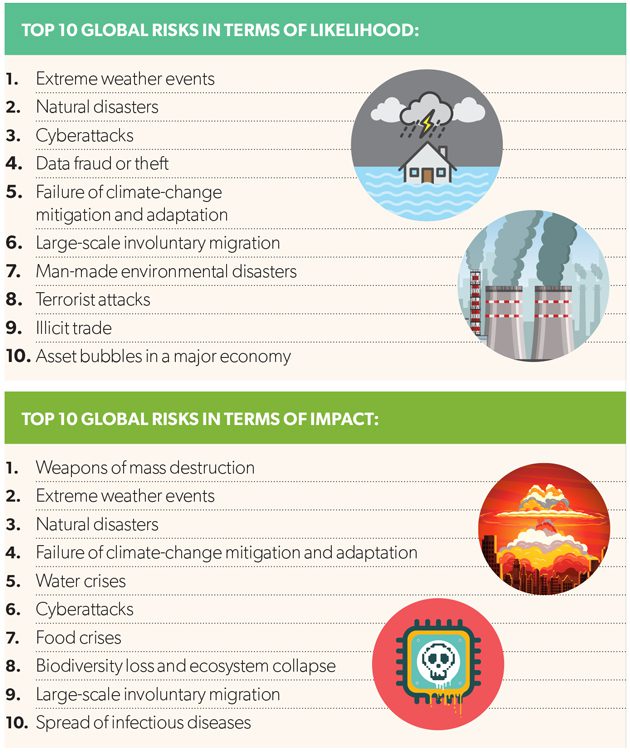

For the second year in a row, extreme weather topped the list as the most likely world threat for the next decade. What’s more, three of the top five risk considered most likely this year are environmental, with natural disasters ranked second and failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation ranked fifth.

Given the record-breaking year for natural catastrophes in 2017, such acute concern over the increasing severity of environmental disasters comes as no surprise. Indeed, according to Aon Benfield’s Weather, Climate & Catastrophe Insight: 2017 Annual Report, 31 billion-dollar weather events occurred last year, generating $353 billion in economic losses, $134 billion in insured losses, and 10,000 human fatalities.

When examining the top risks based on impact, the WEF ranked weapons of mass destruction first, followed by extreme weather events, natural disasters, and failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation. The fifth risk, water crises, already appears fitting as Cape Town, South Africa, counts down to an increasingly imminent “day zero,” when it will effectively exhaust its water supply and become the first major city to run dry.

Two technological threats cracked the top five most likely risks for the first time, with cybersecurity risks rising to become the third most likely global risk, up from sixth last year. The WEF highlighted the increasing financial toll of cyberbreaches, including ransomware attacks, which accounted for 64% of all malicious emails.

“Geopolitical friction is contributing to a surge in the scale and sophistication of cyberattacks,” said John Drzik, president of global risk and digital at Marsh, a strategic partner of the WEF. “At the same time, cyber exposure is growing as firms are becoming more dependent on technology. While cyberrisk management is improving, business and government need to invest far more in resilience efforts if we are to prevent the same bulging ‘protection’ gap between economic and insured losses that we see for natural catastrophes.”

According to Rob Clyde, vice-chair of cyberrisk and governance professionals association ISACA, “While a cyberattack does not qualify as a natural disaster, large-scale attacks are capable of devastating critical infrastructure in a similar fashion. A cyberattack has the potential to disrupt many essential aspects of our lives from electric, gas and water utilities to banking and cellphone coverage.”

Clyde believes organizations should take the report as impetus to assess their cyberrisk policies and procedures. “Possessing these insights will allow boards of directors and executive management to create road maps that make the most sense for their organization and even provide board directors some peace of mind that they are on the right track,” he said.

Data fraud or theft rounded out the top five. The report cited Accenture’s 2017 Cost of Cybercrime Study on the exponential increase in breaches recorded by businesses over the past five years, up from 68 breaches per business in 2012 to 130 per business in 2017. The WEF also highlighted the rising risk of the internet of things, pointing out that there are more of these items—notorious for their lax security—than humans on the planet.

Since the study was first conducted in 2008, the top-rated risks have shifted from primarily economic and geopolitical to environmental and technological. In 2008, the WEF considered the most likely threats in the coming decade to be asset price collapse, Middle East instability, failed and failing states, oil and gas price spike, and chronic disease in the developed world. In terms of likelihood, environmental risks did not crack the top five until 2011 and cyberattacks only made the top five in 2012.

While not in the top five, the prospect of geopolitical conflict was a major concern this year, with 93% of respondents saying they expect political or economic confrontations between major powers to worsen and almost 80% expecting an increase in risks associated with state-on-state military conflict or incursion. The report’s authors noted that “multilateral rules-based approaches have been fraying” and “there is currently no sign that norms and institutions exist towards which the world’s major powers might converge.” The fallout from this escalating rhetoric and uncertainty includes economic and commercial disruptions as well as military tensions. What’s more, these play out in an increasing range of forums, from cyber conflict to reconfigured trade and investment ties. The WEF advised that state and non-state actors alike focus on horizon-scanning and crisis anticipation to account for this dynamic risk environment.

But there is hope for 2018, as a positive economic outlook could be conducive to change if leaders get serious about addressing “systemic fragility.” According to WEF founder and executive chairman Professor Klaus Schwab, “A widening economic recovery presents us with an opportunity that we cannot afford to squander, to tackle the fractures that we have allowed to weaken the world’s institutions, societies and environment. We must take seriously the risk of a global systems breakdown. Together we have the resources and the new scientific and technological knowledge to prevent this. Above all, the challenge is to find the will and momentum to work together for a shared future.”